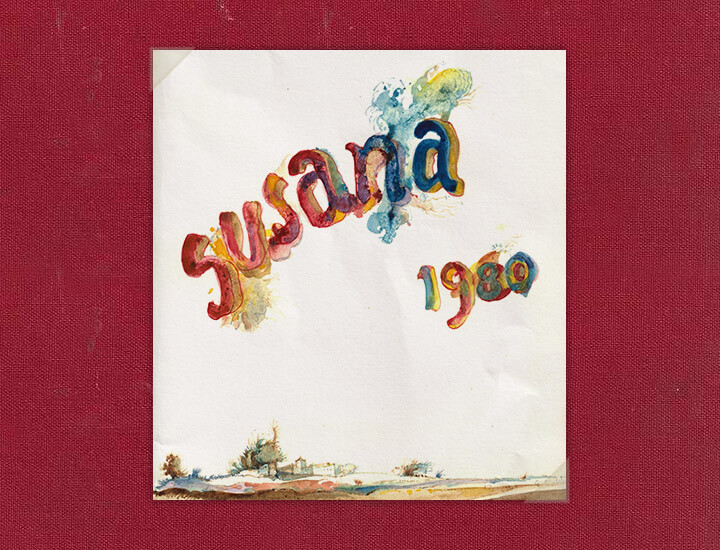

I was already part of Susana and Querubim's lifes for a few months, when I asked Querubim to tell me his story. I sat on the armchair, he sat on the couch. “So, what do you want to know?”, he asked. “Everything”. “No, no. Everything is too much”. I don’t know whether he thought that we didn’t have enough time or that he had already told me too much. I decided to start from the first moment he saw Susana. Grabbing a notepad from the table, he started drawing.

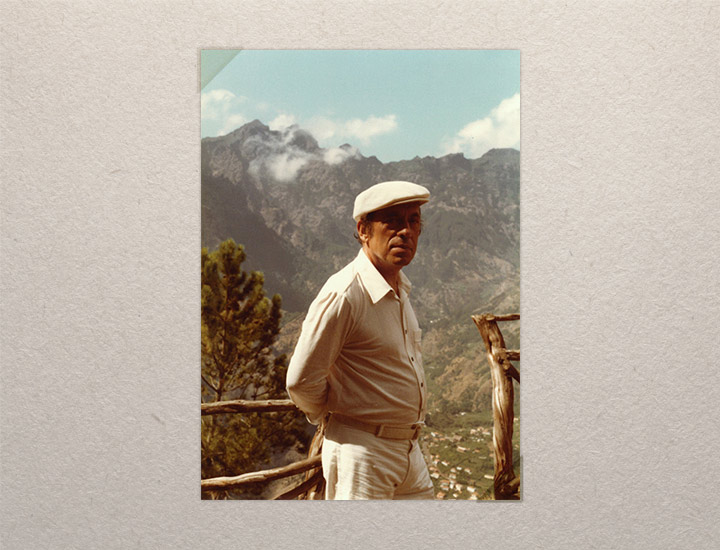

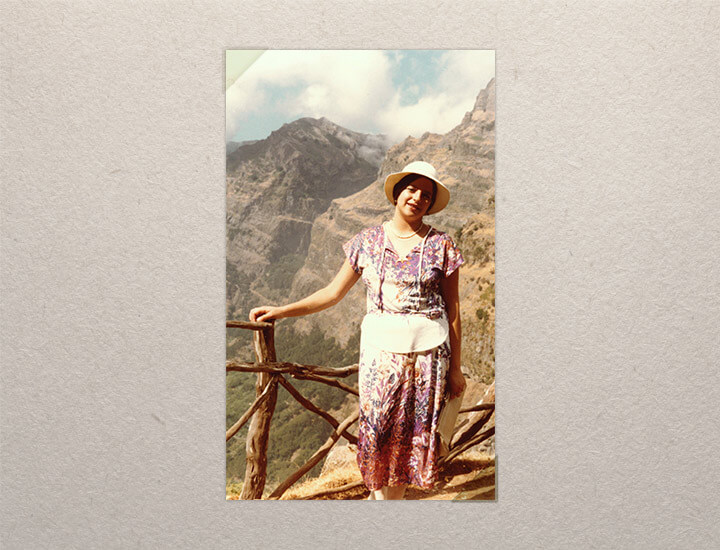

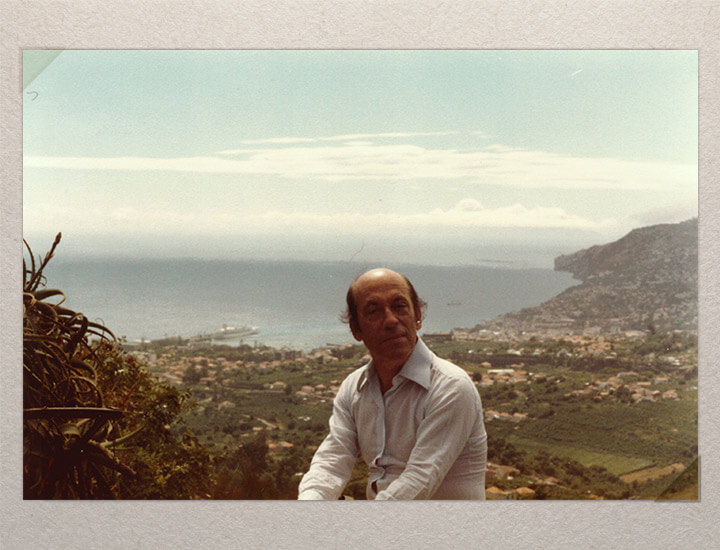

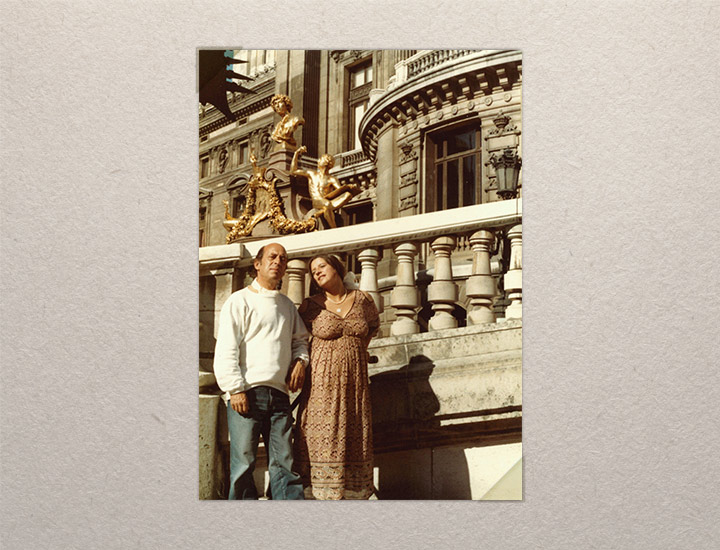

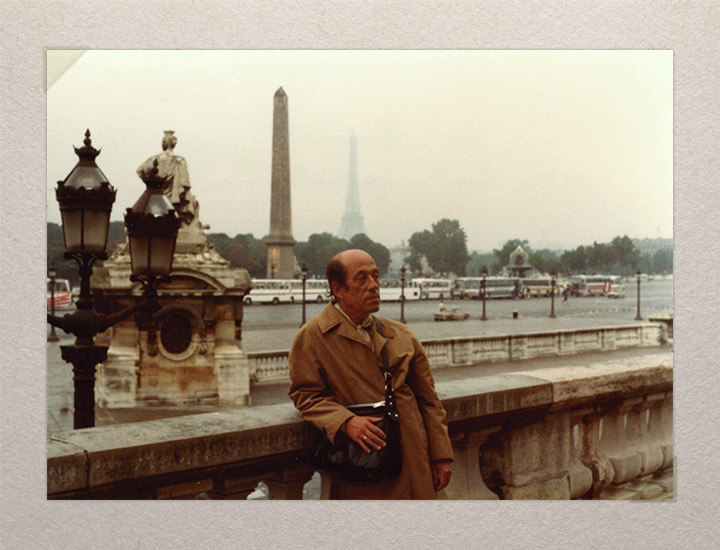

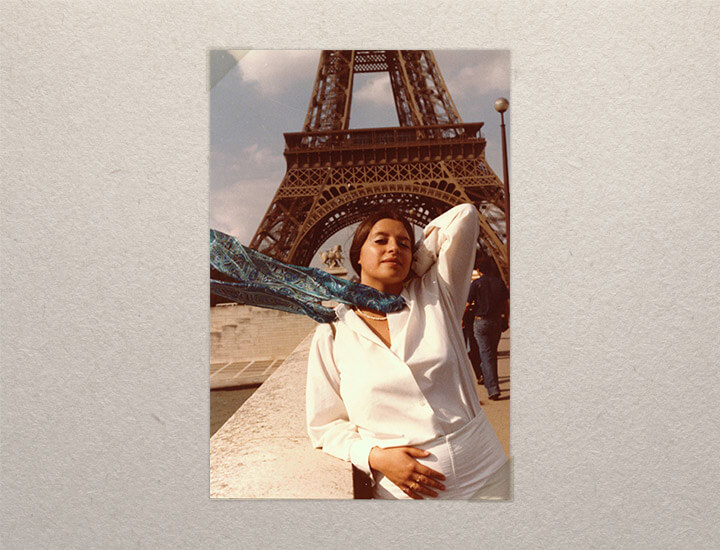

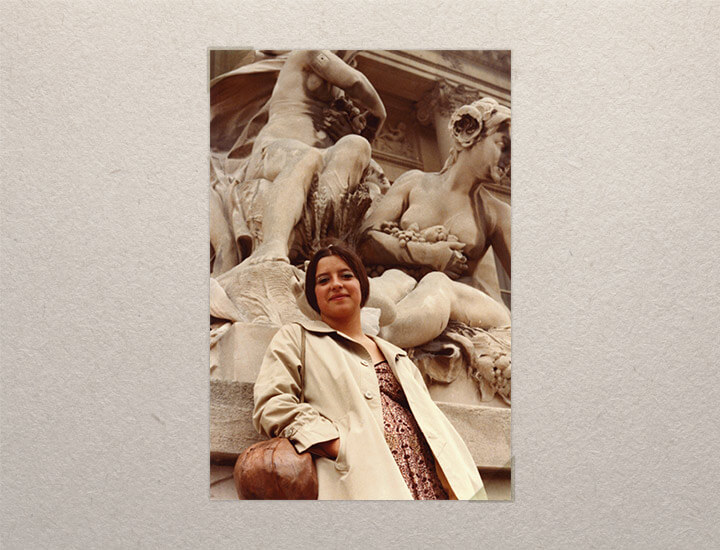

The name Querubim Lapa was familiar but I was not acquainted with his artwork. Now I'd say I knew of the artworks but not of the artist because his work is everywhere: schools, museums, stores or even in the streets. On “Casa da Sorte”, in Chiado, by which I walked by for three years on my way to the University of Fine Arts. Near Alcântara's train station, where I get off to go to work every time I go by train. In September, I was filming in an antiquary, in Lisbon when I met Susana. When she left, Laura, one of the owners, told me that she was the wife of Querubim Lapa, a very important Portuguese ceramist. She also told me that her granddaughter had gone to the couple’s house and had fallen in love with the living room, filled with portraits of Susana painted by Querubim. “Oh grandma, I want a love like that”, she told her.

I decided to follow the story and before I knew it I was already their “adopted daughter”, as Susana called me. “The Pythoness”, said Querubim, who very often liked to explain me the meaning of our very odd names. Although his appearance seemed to be formal at the first, Querubim had a great sense of humor. I was always joking around with him. When he suggested music for the documentary, I told him I was going to use "Mestre da Culinária" by Quim Barreiros ("Master of Culinary", in English, a Portuguese popular music), because he was known as "Master" and was always using wooden spoons and bowls to mix paints. I started singing it and he, without hesitating, sang along with me.

While I was filming, whenever I was behind the camera, he always asked if I was recording. He ended up ruining some takes every time he called me or talked about me. I kept telling him to forget about my presence, but he could only forget about the camera. “Sibila, come here”; “Have you notice this tile? Do you like it?” I woulnd’t answer. And he wouldn’t understand my silence until Susana started mocking him: “She’s filming!”.

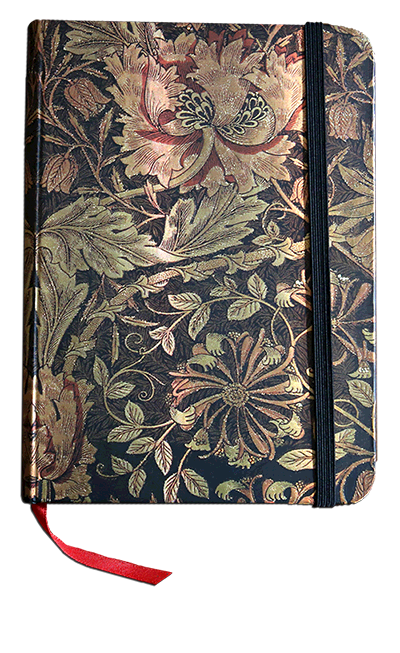

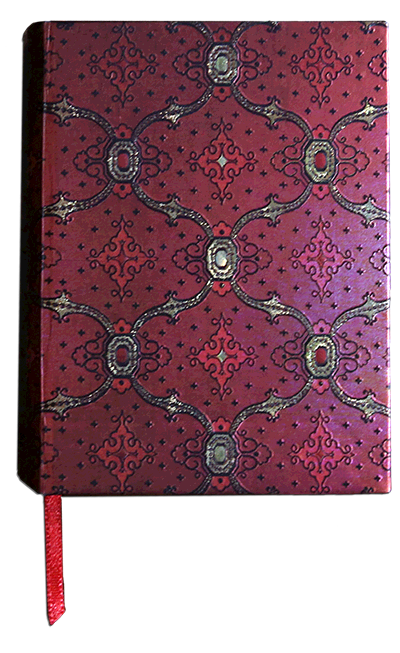

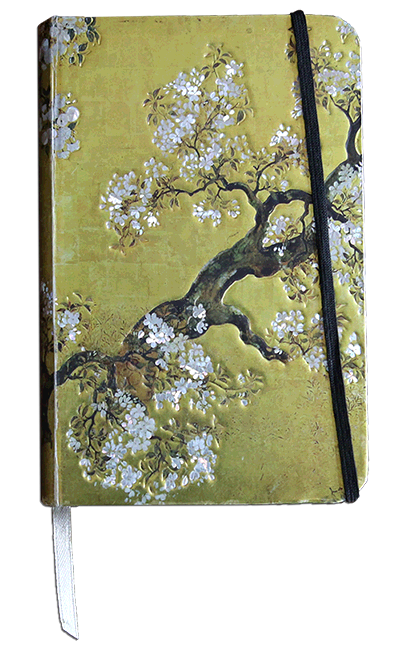

One time while having lunch together, I asked him about death, if it disturbed him. He told me the difference between life and death was being and not being anymore. Almost like going back to the mother’s womb, where we all have been before but don’t remember it. In the living room, he showed me several notebooks where he drew moments he lived or imagined with Susana. “I’ve made two hundred portraits of her”, he told me. “But I’m going to do more”.

When I finished the movie’s trailer, I showed it to Susana. Later, she called Querubim to watch it too. I was afraid he wasn’t going to like it. This project was always about his private life, which he didn’t like to expose. Or, pretended not to like. On those images we could see the life of the artist, but more than his artworks, we can see his intimate, fragile moments, like the time he spent hospitalized with hepatitis, last December. It wasn’t the typical portrait of the artist and his master pieces as icons, but a film about a love story. Holding the smartphone in my hands, we saw it together, the three of us, standing up in the kitchen. In the end, he smiled at me and said: “Thank you”.

Shortly before I finished the movie, I found out that Querubim had the particular habit of writing love sentences and special dedications to Susana on the backs of furniture and artwork. Words that she never wanted to read. Despite the fact that he was 90 years old, I did not expect his death. Nobody did. And I didn’t expect to become so close to him neither. This was supposed to be about his life, “Master” Querubim's love for the arts, but, above all, his love for Susana. And so it will remain. I didn’t make any changes to the documentary. I would have loved for him to see it.

Sibila Lind