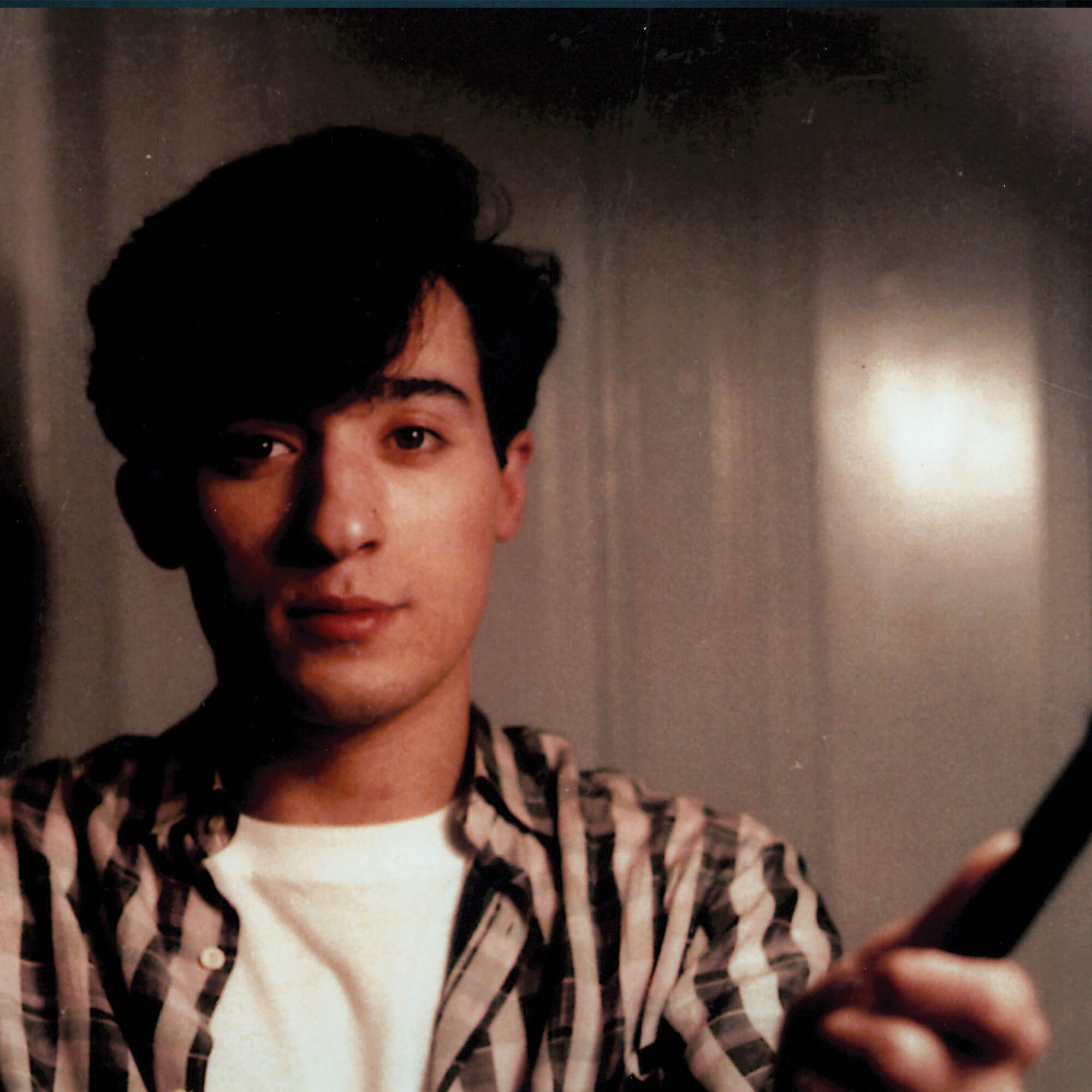

There’s a certain... I don’t know if anonymity is the right word, but there is a kind of indifference that I like in Paris. You can be different, but it’s indifferent. And I like that feeling. As I did when I arrived in Paris for the first time. In Paris I was nobody.

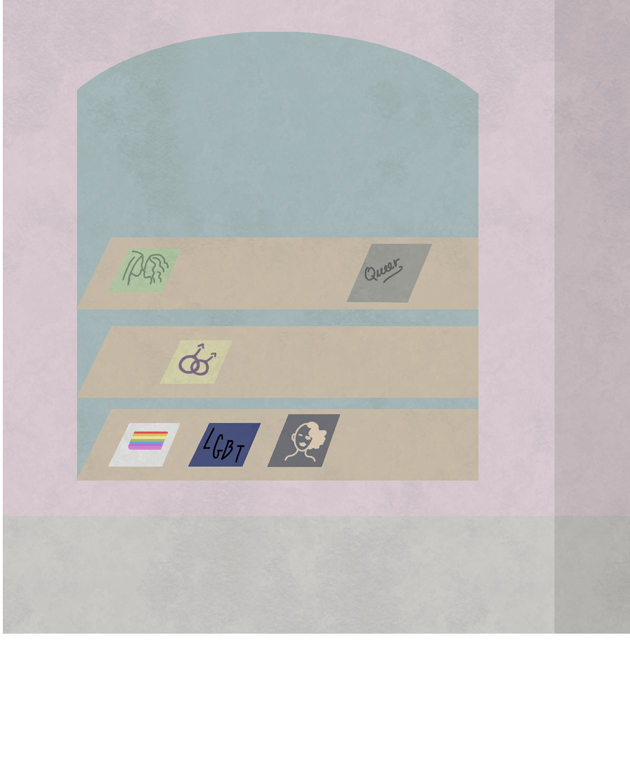

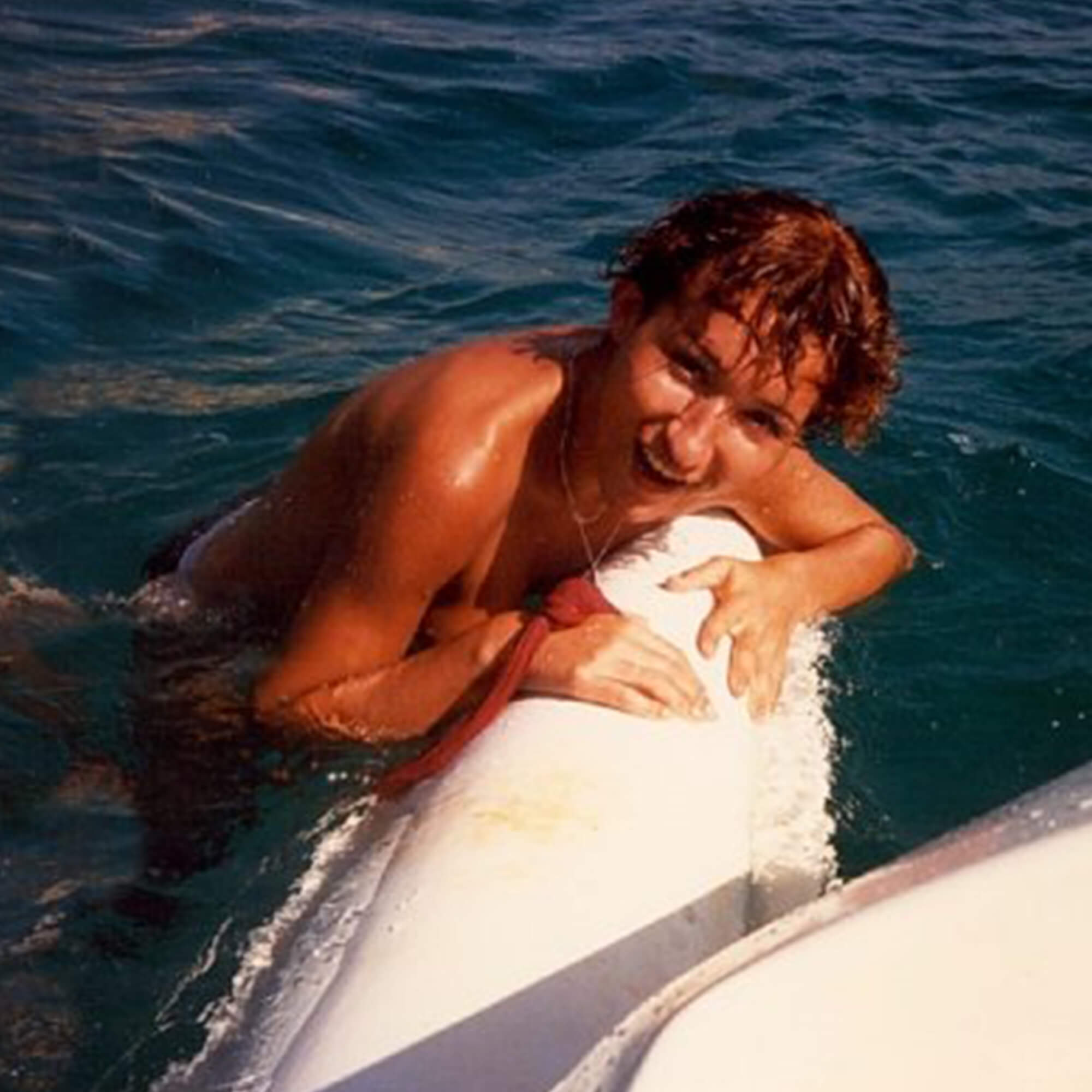

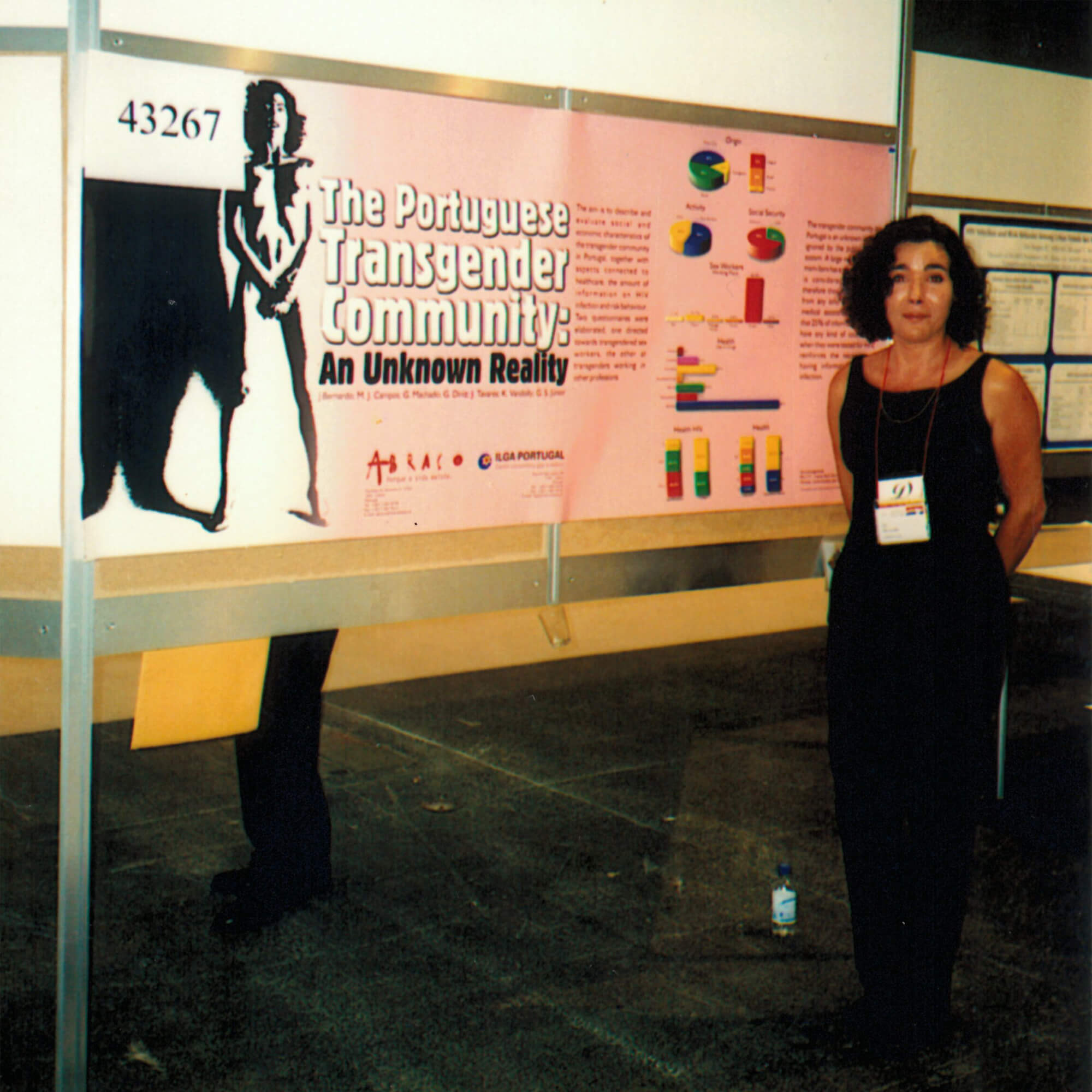

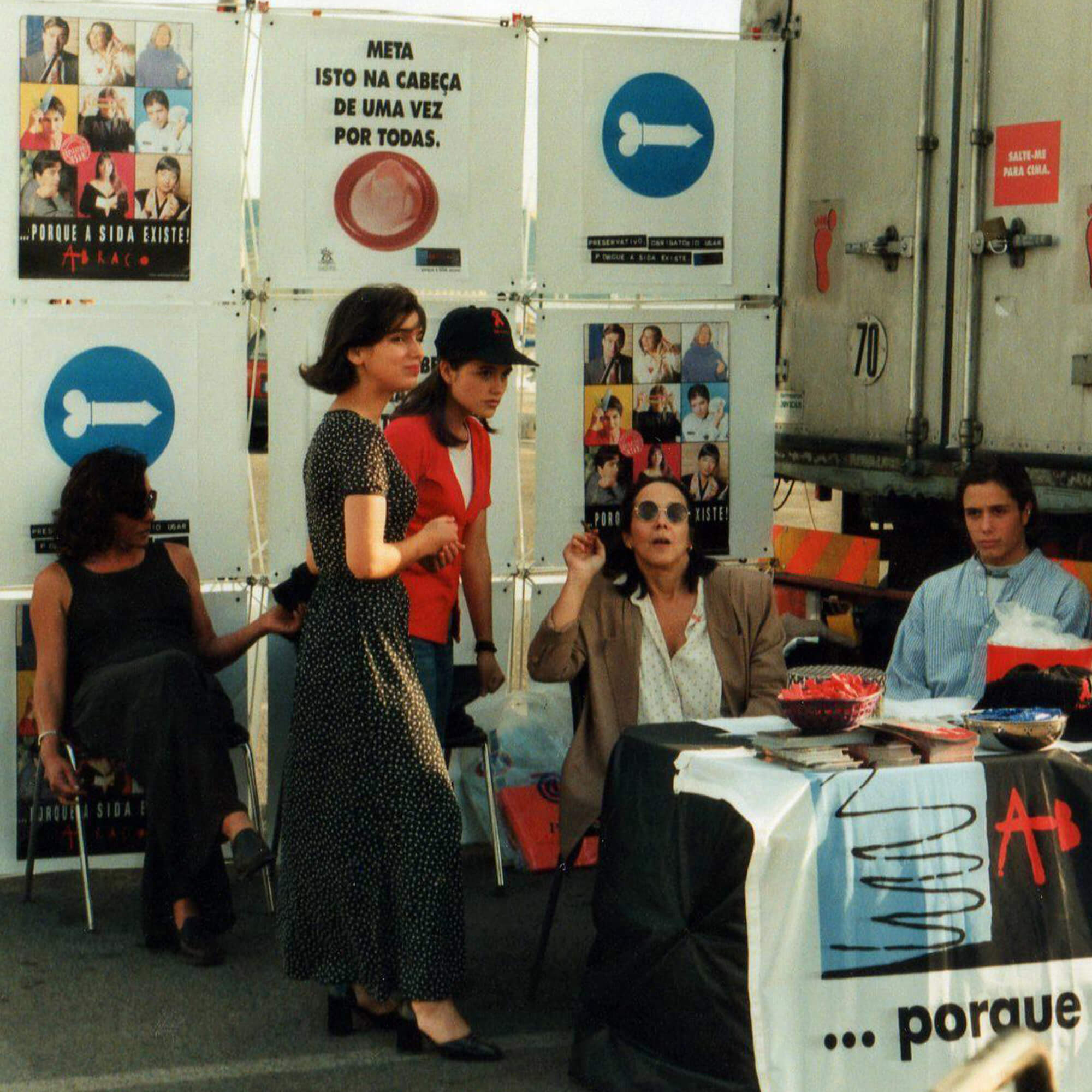

Here, I was the first one to open the first gay bookstore, the first one to create a trans association, the first one to coordinate the first European project about trans and health. The first one, the first one…